2nd Year: The Iliad and the Dynamics of Anger

This is a selection of student reflections in which they reflect on their own personal experience of anger, grief and loss and what the

Iliad could say to them about these things. For this final piece, students had the option of submitting their own creative work.

Jump:

Denise Zhu | Evalyn Richelle Watson | Avery Vojvodin | Maahi Patel

Harsh Patankar | Gallus Mcintyre | Ahsif Khair | Andrew Fullerton | Catherine Cassels

Evalyn Richelle Watson

The

Iliad is, as we know by now, a poem of anger, anger based on personal motivations as well as anger fueled by political and social discrepancies. The actions born out of anger in the

Iliad can be easily related to modern contexts like current wars and social movements but it is most interesting to try to find the right themes in the Iliad to relate to the situation of the world in this very moment. The Global COVID-19 Pandemic connects everyone in the world with a common enemy but that enemy can’t be fought off with anger. This pandemic can only be fought through populations coming together and caring for one another from their own solitary spaces. I have never personally experienced war but it is clear through the

Iliad and countless other texts concerned with war that it is fueled by anger and justice for one's country and values. But now the lives of millions in our world count on the actions of others to put aside prejudice and anger to protect each other. The United Nations have even gone so far as to request a global cease-fire to allow us to fight COVID-19.

The most relevant episode from the

Iliad to our world’s current situation is when Achilles fights the river. Just as the river is a force of nature that Achilles can’t fight, COVID-19 is impossible to fight with anger and action. As scary as it is, Achilles is wrong to disrespect the river by filling it with bodies of his enemies. This instance also reminds me of the choices of many countries in our world to ignore climate change. I know that it is a little bold to connect climate change and COVID-19 but those parallels are very interesting to draw. There are already visible differences in the state of the world regarding pollution since COVID-19 put so much on halt. The air pollution in China has improved significantly and the rivers in Venice, Italy are beginning to clear out a lot of pollution naturally. There are many activists working to raise awareness and spur action towards a world more conscious of climate change. That activism was spurred by anger for the mistreatment of the world’s shared environment and although it did spark some change in individuals’ conscious actions, nothing changed radically enough to impact the unfortunate course we are on with climate change. The last month people across the globe have been asked to work together, isolate and stay inside. This will obviously cause a downfall in the economies of most countries but the change in the pollution levels after just a few weeks of reducing production, driving, and waste can act as proof that we can still change our path and save our planet. It will hopefully give reasoning to this collective anger and make it easier to get through to big companies.

Anger is productive in many cases but just as in Homer’s

Iliad, when you are standing against the force of nature in all its strength and fragility, anger cannot be the only answer. As bad as this pandemic is, hopefully it will provide our world with a turning point to reflect on the anger and disrespect we hold for each other and the environment and lead us to set aside unproductive anger and use the proof we have been given that working together in solidarity is effective to better our planet and foster more love and acceptance into the world. Our world is being hurt by pollution and prejudice and while we all sit in our homes concerned for our countries and fellow humans hopefully we can reflect on which parts of our anger are productive and which parts that are not. Through all this pain and suffering of the world, we are being given a chance to access our rage and anger as societies that have been festering for a long time and, more importantly, the chance to choose what anger and action will be important after this pandemic is over. Achilles and the characters of the

Iliad lived in a world of warfare and fought without a choice. We are living in a world balanced between old hatred and new acceptance but unlike the time of the

Iliad, we are being given a chance to change that even after such a horrible event. I hope we, as a world, make the right choices and move towards productive anger to try to make the world a better place.

<- Back to top

How Auden Engraves New Meaning from The Iliad

Julia Albert

In his ekphrastic poem “The Shield of Achilles,” written in 1952, W. H. Auden vividly describes the making of Achilles’ new shield with desolate and inhumane imagery, in juxtaposition to Homer’s joyous and civilized depictions. Auden distorts the images from their original context in order to comment on the idealization of war and to subvert the empty promises of political authorities who justify wars that often have no winner.

In Book 18 of

The Iliad, Achilles’ best friend, Patroclus, has just been killed while fighting the Trojans on Achilles’ behalf. Upon hearing of his best friend's death, Achilles is distraught and covers himself with “soot and filth”, as if his grief has killed his soul and he wishes to bury his body, despite not having physically died yet (Homer 18.25). Achilles’ devitalizing grief at the loss of his best friend is echoed in Auden’s description of the victims of war, perhaps more specifically Holocaust victims and their family members, who “died as men before their bodies died” (Auden 46). Achilles’ deep sadness quickly turns into uncontrollable rage as he vows to kill Patroclus’ murderer, Hector, even if it means losing his own life. Meanwhile, Achilles’ mother, Thetis, asks “the god of fire”, Hephaestus, to make her son a new shield for his return to battle (Homer 18.720).

In Homer’s description of the shield, Hephaestus carves images of cosmic majesty, scenes of piety and morality, and illustrations of pastoral calm. In contrast, Auden paints images of irrationality and brutality, where “three pale figures” are executed seemingly arbitrarily, where “girls are raped” and where “boys knife” one another (40, 64). Writing after World War II, Auden is offering a political critique of fascist dictators like Hitler and Mussolini who insisted that war was the only answer in order to become prosperous and dominant countries again. Auden assumes his readers are familiar with

The Iliad and that this juxtaposition between descriptions will demonstrate the stark contrast between the fascist propaganda and the horrific reality of the Second World War, which left millions of people killed, displaced, and morally distraught, as well as many women raped by Red Army soldiers in the aftermath of the war[1]. The insistence on war for the sake of restoring justice or reasserting dominance, as Hitler and Mussolini did, is much like the Trojan war, which was launched as an expedition to reclaim Helen, the wife of Meneleus, to the Acheans after she was abducted by the Trojan prince, Paris. Fascist dictators, like Greek warriors of the past, expertly weaved narratives into their reason for fighting and laid out idealized images of the worlds that would result from them winning the battle, like the ideal images Homer describes Hephaestus carving onto Achilles’ shield.

As is well known, the destruction of WWII left much of Europe and Asia in ruins, as many as 60 million people dead, and the ethical repurcussions of dealing with the murder of 6 million Jews[2]. Rather than the idyllic and fruitful images of the shield in The Iliad, Auden depicts the savagery and banal evil that transpired during WWII. He illustrates the lack of empathy that resulted from such fear and propaganda when he describes a young urchin child who does not understand a world “where promises [are] kept” nor where “one could weep because another wept” (Auden 60, 61).

In the 1950s, the Cold War became increasingly tense as the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies became more hostile. With this increased tension, the capacity for mass destruction on a global scale also became foreseeable, as each side innovated their nuclear weaponry. The irrationality and absurdity of the potential outcome of the Cold War, being nuclear annihilation, is also reflected in Auden’s powerful imagery. For instance, Auden describes the paradox of “an artificial wilderness”, which could never logically exist, just as humanity could not logically persist if the Cold War would have concluded as many individuals worried it might in the 1950s and 1960s (Auden 7). Auden’s description of a “sky like lead” might very well refer to the massive atomic and hydrogen bombs that both the United States and Soviet Union had the ability to drop from the sky during these tense times (Auden 8).

Essentially, Auden’s poem urges readers to reflect critically on the atrocities that humans are capable of committing if they fail to act rationally and lose the ability to empathize. He achieves this message by using the literary technique of ekphrasis, in describing the images on the shield that Hephaestus engraves for Achilles in

The Iliad. In distorting Homer’s original joyous descriptions, Auden engraves new meaning into the shield of human history. He subverts political figures who idealize war, and instead demonstrates the illogicality and horror that results from unchecked power and subservient citizens, directly commenting on the political turmoil of his time. Just as no winners are alluded to in Auden’s poem, Homer’s Iliad consistently demonstrates the pain and suffering on both the Achaean and the Trojan sides of the war. Just as Auden yearns for a world where “one could weep because another wept”, Homer too calls for a world of empathy (Auden 61). He recounts the instance between Priam and Achilles in Book 24, when Priam weeps for the loss of his son, sparking Achilles to weep at the thought of his own father’s sadness once he inevitably dies. Ultimately, Auden successfully comments on the idealization of war and all the suffering that comes with it, in an effort to encourage a world of empathy and critical reflection.

~ * ~ * ~

P.S. In Auden’s poem “from In Time of War”, he remarks how “the hospitals alone remind us / Of the equality of man” (Auden, “from In Time of War”). I cannot help but think how the current COVID-19 pandemic reminds us of the equality of humans, who can each be affected by the virus, no matter our nationality, economic status, sexual orientation, religion, or race. Indeed, on CBC’s

The Sunday Edition, Paul Rogers, an expert on international security, mentioned how tensions between Iran and the United States have lessened since the COVID outbreak, and a general diminution of tension in some parts of the Middle East, out of necessity for dealing with each country’s own medical situation. It will be very interesting to see how things progress and what other global conflicts will be put on hold. I wonder how things will resume, and whether we will go back to our old ways once the virus settles down, or learn an important lesson about international cooperation and unity going forward.

<- Back to top

Reflecting on the continuous simile used throughout the

Iliad of Achilles and fire, I decided to integrate the likening of fire to anger within my art piece. After completing each layer, I set fire to it. This method produced a loss of control, burnt thumbs and an abundance of flames as the dry paper and flammable paint were greedily consumed. More importantly, these flames when out, left the pages fragile and brittle. The sheets of ash crumbling leaving delicate bruises of colour on the page below. This process I feel, truly encapsulates the narrative arc of the

Iliad, rage giving way to its consequences, the ashes similar to the fragility of mortality and emotion.

The red pigment is never brought within the body, to illustrate rage as an outward act and our understanding of it as such, instead of located in the body. When external expression of rage is performed, as a society I feel we pay attention, finding the reason to be angry in the other. When allotting the reason to be angry to the self, the holes burn deeper, but they are hidden beneath layers.

Only outbursts are heard, in this thundering world

…

If only we’d listen to a trickle of hurt

|

This artwork has five layers, symbolic of the five we identified within in the

Iliad: spark of anger, consequences, grief, rage and resolution. Additionally, this can transfer to (although contested by Prof. Arnold) the five stages of grief and more generally the layers and complexities of human emotion and behaviour.

The heart, central to this piece and traditionally associated with red tones does not have any of the rage symbolic colour. Furthermore, the heart is left untouched by the charcoal scribbles. This contrasts the disordered ‘scribbles’ over the face or mind and the outward acting hands. The absence of a face was deliberate, I made this decision after reflecting on the presentation from Peter Meineck and the use of masks. There is an absence of brush strokes within the external red to avoid linear lines and thoughts.

As I have covered the majority of my main technical points, I would like to avoid going too in depth to the emotional symbolism etc. and let you, the viewer, interpret and engage without over direction, as to circumvent loss of the ambiguities.

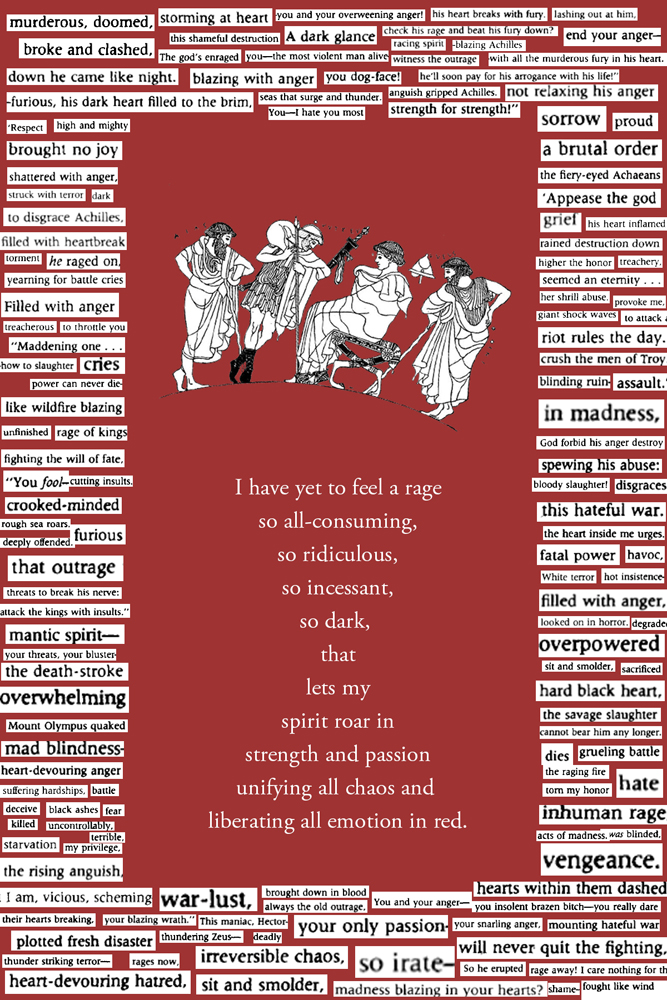

My main goal for this project was the visual element, since I’m not much of a poet! I focused on screenshotting phrasings in Robert Fagles’ translation of the

Iliad that echoed meanings, interpretations, or even literal representations of anger – the goal was to find phrases that resonate with us even in the modern age, to showcase rather explicitly the relevance of Homer’s poem in today’s world. The border of the piece I made is a collage of those phrasings – they contain words, actions, characters’ names, directives, and the beautiful – albeit often repetitive -- descriptions of the focal emotion in question. As for my poem, I wanted to experiment with shaped verse, by mixing my experience with anger or rage, with my perception of it as a multi-faceted emotion. The first half describes rage as reducing and negative, whereas the second half describes it as liberating and cathartic, the verse closing or opening with relation to the emotions in the words. Finally, the image I’ve attached in the center, I found from a clip- art website, which is interesting in that in its form makes accessible what normally is limited to museums or the world of academia - by essentially exposing an ancient piece of literature and its significance to the digital world we now live and experience these very same emotions in.

<- Back to top

Harsh Patankar

Poems:

-

You are chosen

Might, will, strength

You are a holy warrior

Anointed by your stillness

But yet something stirs within you

Fear, jealousy, greed,

Those do not concern you

But something else does burn inside you

A spark for now

So many great men freed from the mortal coil

Can you remain still in the bloodied face of your own mortality

Drink this. Let yourself go

Become something greater

-

It is gasoline

And the fire inside you rages

It will engulf even itself

And in that moment we will see something truly beautiful

The destruction of self

Rise, and eat the sun

Cast them in darkness

So they see as you do

-

Did you really think you could quench hell’s flames?

Were you so certain you would remain whole in this ordeal?

Pick up your hellblade, you resigned yourself to this fate

Raze the world in fire, but let those who once loved watch

Kindling, for when the fire must rage anew.

<- Back to top

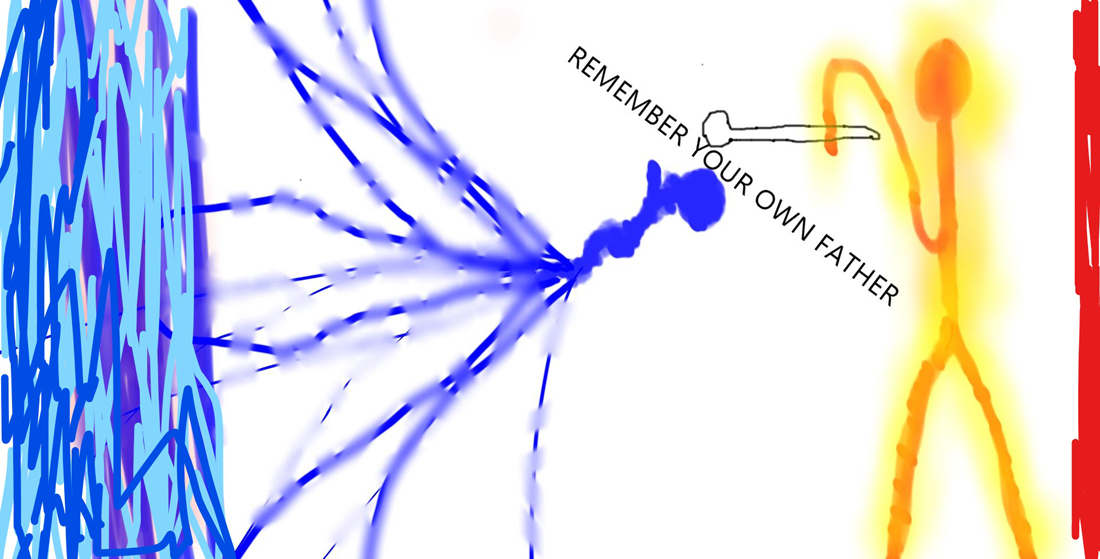

Remember Your Own Father

Gallus Mcintyre

Remember Your Own Father is my first attempt at producing a work of visual art. For this final project, instead of looking at the

Iliad holistically, I decided to look back at the various plot points, and do an artistic depiction of one that spoke to me particularly deeply. I decided, after some contemplation, that this was the final scene where Priam asks Achilles for the return of Hector’s body. This scene was one of the first to come to mind given that I voice recorded Priam’s monologue for this scene, which left it fresh in my mind. Also, in having to voice record this scene, I was made to carefully consider Priam’s words in order to accurately and effectively

reproduce his monologue. This involved putting more of an emotional emphasis on some sentences, adjusting tempo in accordance with a rise in emotion etc. Due to this process, I came to understand Priam’s emotions well, as well as the dynamic between him and Achilles. This scene is extremely emotional for a number of reasons and I tried best to encapsulate this in both my voice recording and abstract rendering of it.

So, as anyone who’s familiar with the

Iliad can immediately identify, the figure in the red is Achilles, Priam is in blue, and Hector is merely outlined. Hector is void of colour so as to show his lack of any emotion/ interest in this dynamic. He is neutral, as he is dead. Since colour has been used in the piece to reflect emotion; Hector has no emotion, ergo, he has no colour. Achilles has been made considerably larger than the other two as a means of exemplifying the power he holds in this situation. To further illustrate his power, I incorporated a yellow hue

around his body, something that is commonly associated with awe-worthy/powerful and even god-like figures. In this scene Achilles is very much like a God in that he is extremely powerful and completely in control, making this illustration of him appropriate. What is also notable in Achilles’ rendering is that he has legs. Not only does this make his figure larger than the others, but this shows his stability in the situation. He is firmly in place while the other two figures are suspended in space, a further illustration of his power.

As for Priam, I tried my best to associate weakness and vulnerability in his depiction. Priam, as a king, has likely never been in a situation in which he needed to beg someone else for something he desired. Given this, in begging for Hector’s body Priam has taken an unfathomable injury to his pride and is miles out of his comfort zone. Note that in contrast to Achilles’ upright posture, Priam almost looks like a worm. Also take note of his hand that is

helplessly reaching towards his son’s body, as Achilles effortlessly dangles it before him.

The blue rectangle behind Priam is my depiction of Troy. Note that it has been infused with a red hue; this is symbolic of Achilles’ influence on the city, and the grief and disorder he has incited within it. The red in behind Achilles is symbolic of the Achaean camp. While this exchange is based on the Achaean camp, I felt inclined to depict Troy and the Achaean camp on opposite ends of the frame so as to communicate their ongoing opposition to each other. The blue lines coming from Priam’s body intend to illustrate the internal conflict Priam is having as he reaches out to Achilles for sympathy. These illustrate the fear of being denied, the hit to his pride, his vulnerability, and all these factors that work collectively to discourage him from approaching Achilles with this request. Due to them discouraging him from his encounter with Achilles, I made the point of connecting these lines to my depiction of Troy to give the impression that they’re trying to pull him back towards his home. I used the blur effect haphazardly over these lines to illustrate the chaos in this internal conflict of Priam’s.

The words “Remember your own father” have been incorporated into the piece between Priam and Hector’s body. I chose to incorporate this quote because it, rather than the ransom, is largely what motivates Achilles to return the body as he is made to sympathize with Priam. I placed the sentence between Priam and Hector because it is what essentially ends up connecting them as the body is handed over to Priam on account of this statement.

<- Back to top

"A Troy Story"

Ahsif Khair

It’s the eyes that give it away.

That death-stare is unbecoming of you.

Some light from behind--extinguished, signifying a person vanquished.

Yet, what has changed?

—all the pieces are here.

Is this you?

It has your eyes, your lips, and hair. And still--

It is an abomination

to give it your name.

Some essential component is lost,

with it the function of this delicate machine.

Are you having suicidal thoughts?

They ask not seeing my heart,

this blood pumper in that place so dark.

Downright homicidal is my art.

Then rage on, lion hearted man.

Bury your chest in the enemy’s pain;

It rings out in paeans, brazen and bold.

To kill that motherfucker.

You will need bronze and balls.

Lift your soul out and leave it there

in the blood of the unworthy.

Now the stage is set

for the furies to sing the rage.

All other things to the side are set,

now is the time to open the cage.

I hope I don’t offend your sensibility.

But again, I’m reminded

I don’t give a shit.

Now for a riot, a ruckus, a brawl.

Here is the time for empires to fall.

That night I got a call, Drunken with bloodlust

A brother, a god, asking for hell

Today I am a killer.

You couldn’t understand the pangs of a hero:

deep in the heart, the warrior calls

warring against divine inclination.

Beating on my chest,

I am my own war drum.

Achilles tonight,

And Priam tomorrow.

For the things gone and dead

I will strike, and behind me

the goddess sprung from the head.

Even still I throw tactics to wind.

Tacit rage, to no whim that will bend

last of all my own.

Are you ready?

Now the bloodletting begins.

Cacophonous chatter, falling on deaf ears.

Ignoring almost all I pick out a wonderful song.

The horse-breaker speaks in lyric,

his shrieking and his piteous eyes will sing my pain.

Though the songs of the muse speak louder still

than the pleas of my prey.

Routed in the field, he knows he is defeated.

Standing over him, god’s butcher

brandishing his lethal fangs.

His pathetic pleading is his last protest

against his bondage.

There are no pacts between men and lions.

Now my eyes are all cried out,

and sleep has brought morning.

Rosy fingers brush away rage,

and pitiful mourning.

Though the deed is done and revenge exacted,

the muse still sings.

More blood to be spilled,

the day's labours lie before me.

It isn’t over, but that’s the whole story.

<- Back to top

"Seeing Myself Through Achilles: A Self-Indulgent but Honest Introspection"

Andrew Fullerton

Whereas godlike Achilles chose angrily to remove himself from the field, thus causing the immense and prolonged suffering of his mortal Greek comrades, that is exactly what we, the hyper- immune young people of society, must do in order to protect the young, the elderly, and the immunocompromised during Canada’s coronavirus outbreak. It is only in inactivity, in withdrawing from our usual presence in society that we can aid those at risk. Selfishly though, I feel that I, like Achilles, am navigating feelings of anger and injustice at my circumstance. In a circumstance that necessitates the idling of the young and the active, myself among them, I can’t help but observe that the nature of my anger coincides with that of Achilles.

Achilles’ rage is born of a lack of recognition of his contributions to the Greek army, at Agamemnon for robbing him of his prized woman, Briseis, and of a lack of acknowledgement for his sacrifice on account of his efforts in battle: his mortal existence. My anger at this time too is fueled by a lack of recognition for my own sacrifices at this time. I feel self-centred and inconsiderate on account of my anger but at times powerless to it nonetheless. With each adult of an older demographic who peers resentfully at me and pulls a scarf or sweater over top of their mouth as I walk through the park, and with those interactions like one I had recently with a woman at the grocery store who requested that my girlfriend and I be removed from the store on account of being young people, as though we were personally responsible for all young people who may be transmitting coronavirus without personally suffering its consequences, I feel myself entering an anger like that of Achilles. To keep those members of at-risk demographics safe, I have sacrificed, like many others my age. Unlike Achilles my sacrifice is not a physical one though. What I sacrifice through my inactivity and my isolation is my mental health and through it I find myself connecting to Achilles at this time.

Just as Achilles’ physical prowess permits him glory in battle but also restricts him to a short life, it is the nature of my anxiety, its restlessness and its obsessiveness, that allows me to exert myself to the fullest every day. In idle-state and isolation though, this nature renders me despondent, a dismantler of myself. As I suffer the repercussions of my gift in isolation, I identify Agamemnon in the aforementioned demographic paying me no gratitude, refusing to recognize my sacrifices, and unwilling to show gratitude on account of those sacrifices. Like Agamemnon’s taking of Briseis, stripping Achilles of that which he sees belongs to him by right, fueling his anger and withdrawal from battle, each scold I earned during my single trip to the grocery store since emergency measures were instated, and every resentful sentiment I feel directed upon me during my morning walk, my only outing each day, I feel stripped of my rights as a human being. I feel stripped of the right to buy food and I feel stripped of the right to go for a cautious walk, even at social distance. I feel stripped of the right to take break from the anxiety I am fighting today, and which I fought yesterday, and will continue to fight for the foreseeable future.

This feeling of injustice that I have right now makes me angry. That anger makes me want to retire my own efforts to self-isolate, just as the rage of Achilles drove him to withdraw from battle, leaving the Greeks to suffer on their own. Yet through Achilles I am also finding the foresight necessary to continue my efforts to self-isolate. On account of Achilles’ rage and withdrawal, Patroclus met his death against the Trojan army. Through the death of Patroclus I see that I must fulfill my duty and continue to make sacrifices, not on account of any acknowledgment or gratitude. Instead, I see that I must self-isolate on account of the good men and women of society, the healthcare workers who are putting themselves in harm’s way on account of those who are unable to avoid harm’s way, the immunocompromised and the elderly. It is my duty to the Patrocluses of our society at this time to do all that I can to protect those at risk, and just as Achilles suffers the repercussions of his gift in doing so, I owe it to them to suffer the repercussions of mine and fight on against my anxiety.

<- Back to top

For my final reflection on

The Iliad, I chose to create a collage-style artwork. The central image of the work is a clipping from Gavin Hamilton's

Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus (1760-1763). I chose the image do depict the combatting feelings of rage and grief that Achilles feels after the death of his beloved companion, and find the Hamilton piece to be immensely moving. I printed and painted the image, with Achilles red with rage, and Patroclus blue for grief. Achilles' arms begin to turn blue where he holds Patroclus' body, representing the struggle between the two emotions.

To highlight the themes of rage and grief, the right side of the collage is pasted with red images, and the left, with blue. I tried to make the colours look almost combative, with Achilles almost pushing back the rage on the right, letting the grief on the left in momentarily.

On the red side, there are images of fire, and powerful animals worked into the background, common symbols of anger, maleness, or pride, like the tiger and the snake. There are also some images of women, though partially hidden. The tiger covers the face of one woman by Achilles' leg, almost consuming her. Achilles covers the face of the woman with his arm, almost silencing her. Similarly, the women in

The Iliad are often overpowered or have their opinions silenced by men, like Helen, Andromache, and even the Goddesses by Zeus.

The blue side includes images of ships, the ocean, homes, and statues. This is representative of Achilles' acknowledgment, lamentation, and acceptance that he will never return across the ocean and back home on the ships with the other Acheans. He knows that his decision to go back into battle will fulfill his prophecy of death. The statues represent the commemoration and immortalization of all of the fallen and passed in the Trojan war. When Achilles lets in his grief, he can mourn the losses of the many other lives that have gone but not been forgotten during this war.

Finally, though it is hard to tell in the photos, I have outlined both men in gold glitter, and their halos. While halos are not traditional to Ancient Greek culture as a Christian image, it is a meant to be a more modern take on the idea of what is "god-like." This is to represent the "god-like" nature of Achilles, hence his bold halo and the direct reference to Jesus above him. Patroclus' halo is more subtle, as he is not a God or a Demi-God, but to Achilles, was god-like, as his best friend and loyal companion. The halo is meant to show how Achilles saw his friend.

Rage and grief control Achilles and all of his actions throughout

The Iliad, and I feel my picture could represent how powerful, and exhausting, these combative emotions were in the pivotal scene of Patroclus' death.

<- Back to top